Executive summary:

Western Woodblock Printmaking uses oil based inks applied to the block with a brayer (roller), and the blocks are sometimes printed with a press, and Japanese Woodblock Prints (aka Moku Hanga) are made with water-based inks applied with a brush, and are printed by rubbing a pad (baren) across the back of the paper.

Disclaimer:

Before I go on, I should make a little disclaimer: I’ve never made a Japanese Style woodblock print. Everything I know about it is from research, reading, and viewing Japanese Woodblock Prints. As a result, I might be a little irreverent.

Also, I am going to use the terms “Japanese Woodblock Printmaking” and “Moku Hanga” interchangeably. Moku Hanga translates to something like “wood pictures” or “wood graphics”, and is the Japanese name for printmaking.

Ink, Wood and Paper

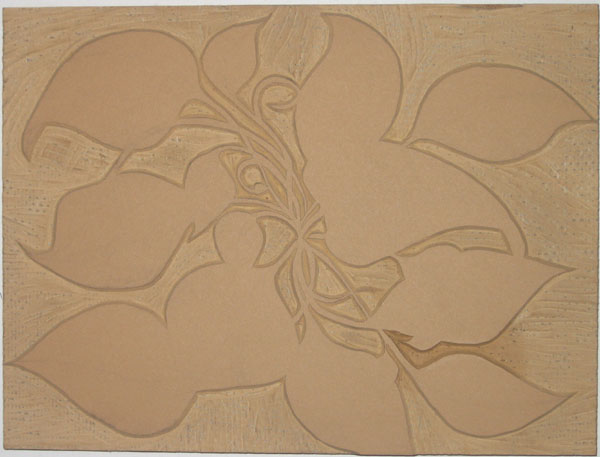

Woodblock Printmaking is the art of using wood to mash ink onto paper. By carving the block of wood, you can control where ink is applied to the wood, and as a result, where it is mashed onto the paper. Sure, it gets complicated as you add detail to the image, and as you carve multiple blocks to include more colors in the print. Basically, however, it is the same principle regardless of how much detail you include. Mashing ink against paper is mashing ink against paper no matter how you spice it up.

…and no matter where in the world you do it.

There aren’t really many differences between Moku Hanga and Western Woodblock Printmaking. The biggest difference is that Japanese Woodblock Prints are, well, Japanese.

Moku Hanga

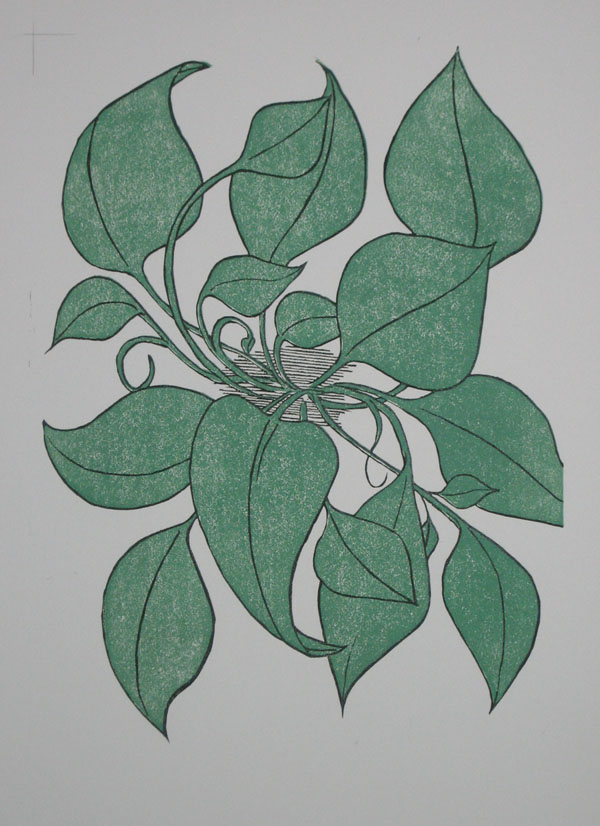

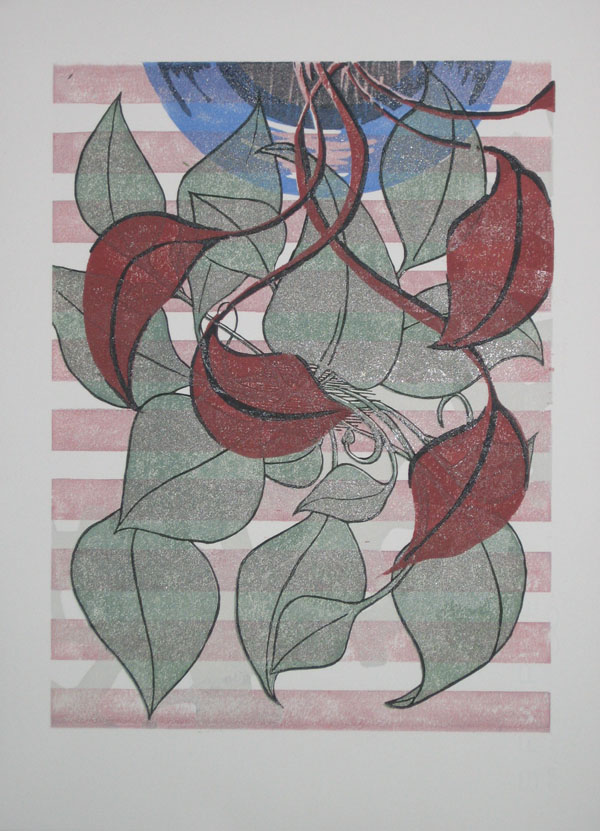

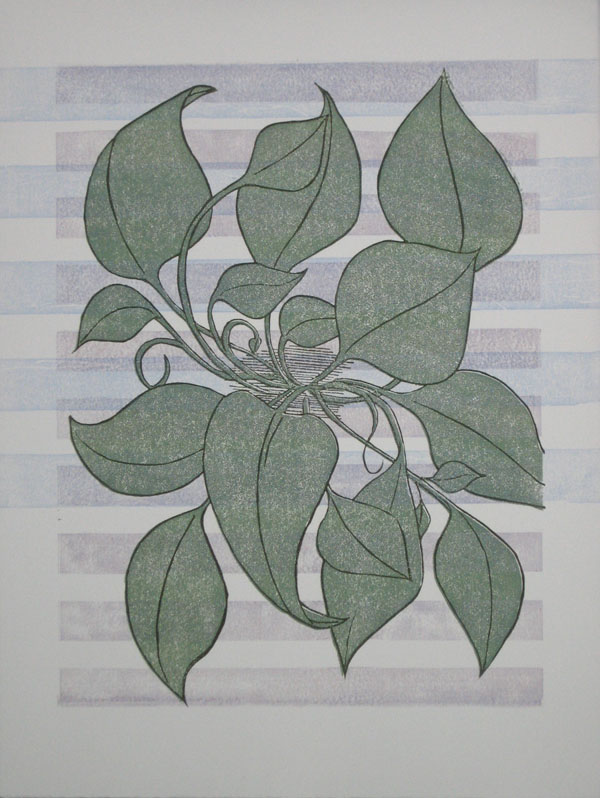

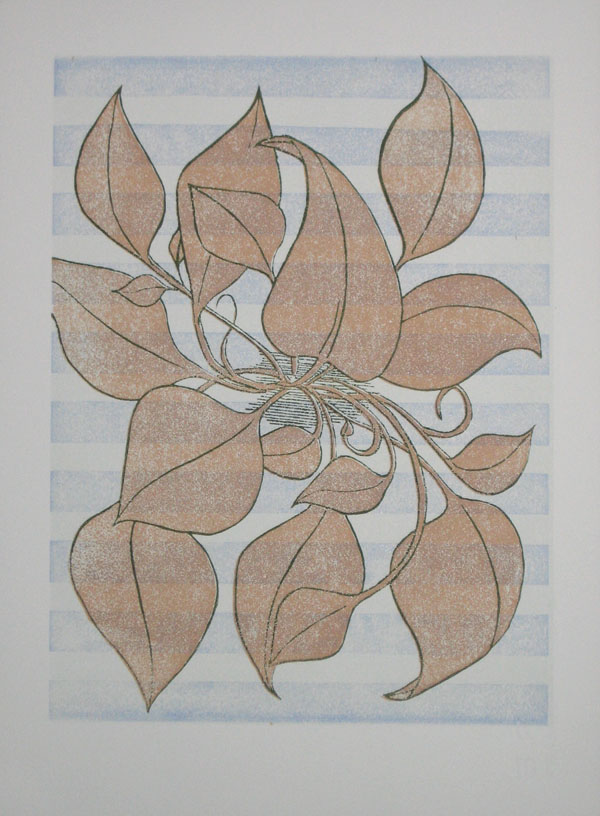

Japanese Woodblock Prints use water based ink. The water-based inks used for Japanese Woodblock prints give them a particular texture and quality that I have trouble describing, other than to say “it looks like a Japanese Woodcut”. The technique used to print in the Japanese method results in a little more texture than western methods, because the ink is applied by hand. This leads to a little variation in the density of ink throughout the print.

Speaking of “method”, it is the methods that really make a Japanese Woodblock Print what it is. Moku Hanga uses specific carving tools, which all have very specific names. Each specific tool (with its specific name) is used for a specific task.

Registration is done in a specific way, by carving very specific notches into the woodblock. Each of those notches has a specific name too (kagi and hikitsuke).

The paint is mixed in a very specific way, and applied to the block with a specific type of brush. You use a baren to press the paper against the block, to transfer the ink to the block. [Note: a “baren” is a handheld pad used to rub the paper against the block to transfer the ink] There are different barens for different uses.

Japanese Woodblock Prints are printed on a particular type of paper, called Washi, made in a particular way. This is sometimes called “rice paper”, even though it is not made of rice. It is very thin and delicate, however.

The emphasis on method and tradition is very Japanese (for lack of a better way to describe it). It reminds me of the Japanese Tea Ceremony, where everything is done in a particular way, with particular tools.

Western Woodblock Printmaking

Compare this to Western Woodblock Printing, where it seems that by comparison, anything goes. Use whatever roller you want to apply the ink. Any registration method will do, as long as it works. Press it by hand or run it through a press. It’s all good.

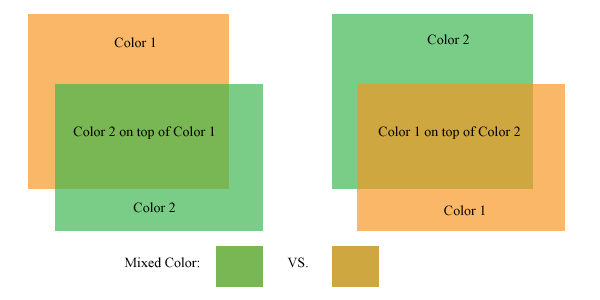

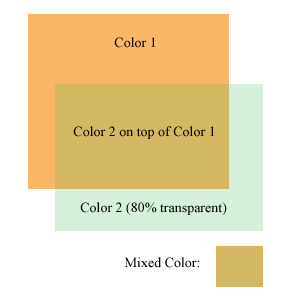

The ink used in western Woodblock Prints is typically oil based, though there are some modern water based inks that are designed to imitate the look and feel of the traditional oils (makes everything less messy).

Ink is applied with a brayer (ie. a roller), which results in a very even and smooth application of ink.

Washi paper is sometimes used, though other papers are also used. Rice paper is not required.

Not much difference

So, what is the difference, other than some very specific traditional ways to do things, and a difference in ink?

The answer is, “not much”.

I may sound a little irreverent about Moku Hanga, please don’t get me wrong. Japanese Woodblock Prints are some of my favorite art from throughout history, and throughout the world. This is merely my perspective from my point of view as a Western-style printmaker.

The goal of each method is to make beautiful art. The process is pretty much the same: Wood, ink, paper. Apply and transfer. Repeat.

Make beautiful art.