Or…

Things Fall Apart… When they are forcibly disassembled

The modernists went as far as they could go, they proved the thesis of Modern Art – art didn’t have to have subject matter, it could be a “pure” creation, subject matter and the materials used to make it were one and the same.

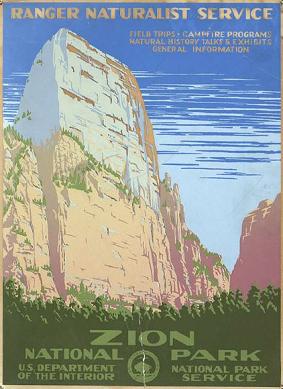

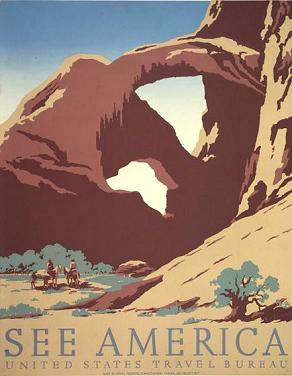

In the 1950s, a couple of upstarts thought that was boring, and did something different, and they drew (no pun intended) subject matter from ordinary, daily things. Flags, numbers, soup cans, and shoes. Pop Art was invented.

It’s hard to explain how Pop Art was a radical departure from modernism, but the main departure was to say, “art isn’t some hoity toity, amazing thing, a reflection of ‘high’ culture; anything can be art”.

And then all hell broke loose.

Honestly, it is hard to write this entry of my “short, irreverent” history, because so much happened in the 1960s, 70s, 80s and 90s that was so different from anything that had previously been called art, it doesn’t fit into a linear narrative as well as Modern Art does. It was an explosion that went in many directions at once.

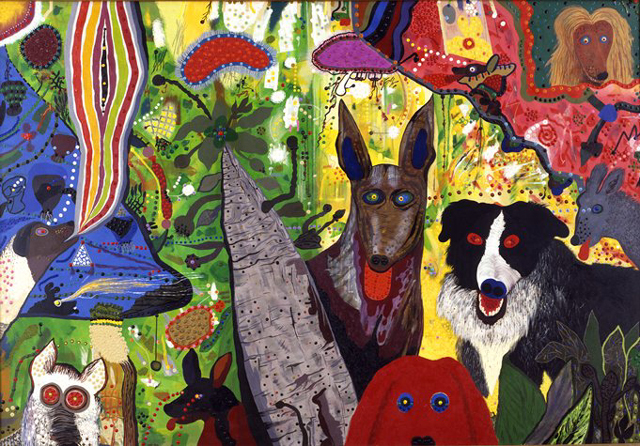

There was performance art, installations, pop art, assembelage, video, conceptual art, digital art, and other bizarre ways to make art. Art addressed gender, nature, consumerism, space and environment, kitsch, and religion.

A lot of art from this time was “shocking” (link is NSFW), and a lot of people would say, just plain strange or uncalled for (another not quite SFW image). Often, when people see post-modern art, the response is, “how is this art?”

It seems like art became random in the post-modern era, but I think there was a common thread, just like there was a common thread in the Modern era. The thesis of Post-Modern art is that there isn’t a distinction between art and life. Anything can be art, if attention is brought to it as art, and anything that was art could be part of life.

Art wasn’t a “thing” to be “made” that would sit in a gallery or museum to be looked at when someone wanted to “experience art”, it was something that happened all around us, all the time. Life is art, and art is life, it has the meaning that we give it, and it obtains meaning when we draw attention to it.

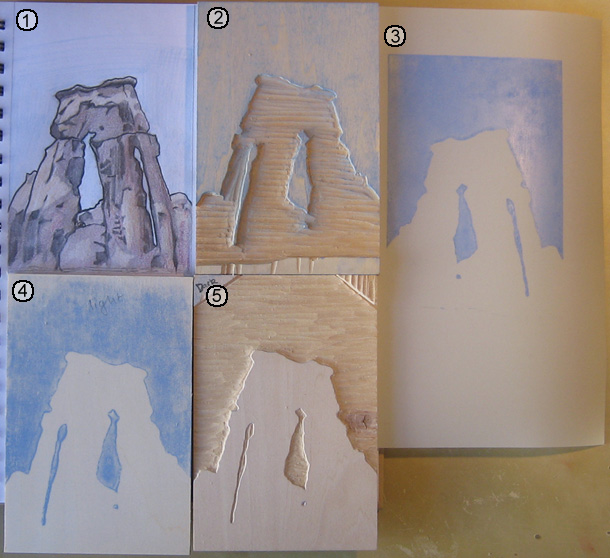

The wall between art and life was brought down. Post-Modern art disassembled the meaning of art, each movement and method unravelled the meaning of art in a different direction.

That’s pretty damn cool.

The problem is that it leaves art completely deconstructed, completely disassembled, lacking any definition and structure. This sucks for artists now.

There are a whole lot of pieces laying all over the floor now that the post-modernist are through with it. It is the morning after a raging, drunken party, and we wake up, the house is trashed, and we have the mother of all headaches.

Up next, the fallout, and where we are now.